Evaluate whether your sign meets the distinctiveness requirement before filing.

Calculate the quote

The legal battle between Adidas and Thom Browne has moved beyond the issue of likelihood of confusion. Although Adidas initially lost its opposition, the dispute took an unexpected turn: with decision R 689/2024-2 dated 1 April 2025, the Second Board of Appeal of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) decided to re-examine the figurative trademark filed by Thom Browne for a potential lack of distinctiveness. The reason? Its red, white, and blue stripes might be perceived as a mere decorative element. What is at stake is not just a logo, but the very ability to protect a stylistic element as a trademark. This is a highly relevant case for those working in fashion, branding, and intellectual property.

In the fashion world, style is everything. But in intellectual property law, style alone does not guarantee trademark protection. This tension is now front and center in the legal dispute between Adidas and Thom Browne—two brands with distinct identities but clashing over a series of stripes.

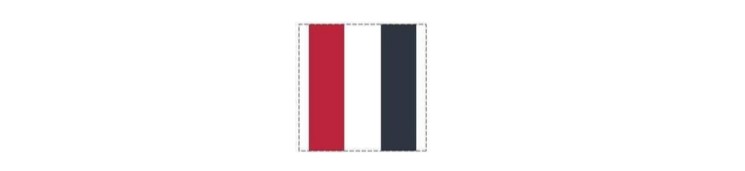

In 2017, Thom Browne—a renowned American designer—filed an application for a figurative trademark featuring five vertical stripes (white, red, and blue), enclosed within a dashed-line rectangle. The mark was intended for use on clothing, handbags, and fashion accessories.

Adidas opposed the application, arguing that there was a risk of confusion with its iconic three-stripe trademarks, which are widely recognized in the sportswear and casual fashion markets.

In January 2024, the blow came for Adidas: its opposition was rejected. The Opposition Division of the EUIPO found no likelihood of confusion between the marks. According to the Office, consumers would not associate Thom Browne’s design with Adidas. A full victory for the American fashion house? Not quite.

Adidas appealed the decision, and in April 2025 came the plot twist. The Board of Appeal announced that the case would no longer focus solely on Adidas’s prior rights or the risk of confusion. A more profound issue was now at stake—one that could be even more dangerous for Thom Browne. His red, white, and blue striped design might entirely lack distinctive character and thus fail to qualify as a valid trademark.

So, while Adidas may have formally “lost” on the initial opposition, the entire legal proceeding took a different turn. It is no longer just a dispute between two trademarks: it is the very existence of Thom Browne’s mark that is now in jeopardy.

Come chiarito nella decisione R 689/2024-2 del 1° aprile 2025, la Commissione ha ritenuto che il segno richiesto da Thom Browne – pur essendo graficamente definito – potrebbe non presentare caratteristiche sufficienti a distinguere i prodotti di un’impresa da quelli di un’altra, come richiesto dall’art. 7, par. 1, lett. b) RMUE.

As explained in decision R 689/2024-2 dated 1 April 2025, the Board of Appeal held that the mark filed by Thom Browne—although graphically defined—might not possess enough features to distinguish the goods of one undertaking from those of another, as required under Article 7(1)(b) of the European Union Trade Mark Regulation (EUTMR).

Trademark law recognizes two broad categories of grounds for refusal: relative and absolute.

Relative grounds are typically asserted by holders of earlier rights, as Adidas did, claiming that a new sign is confusingly similar. Absolute grounds, however, may be raised ex officio by the EUIPO and concern the intrinsic legal validity of the sign itself.

This is precisely what happened in this case. After receiving Adidas’s appeal, the Board recognized that the issue might not be whether the mark resembled Adidas’s own, but rather whether Thom Browne’s sign should have been accepted for registration at all—because it lacked the fundamental requirement of distinctiveness.

To be valid, a trademark must be capable of distinguishing a company’s goods or services from those of others (Art. 7(1)(b) EUTMR). A visually attractive or well-crafted design is not sufficient: it must be perceived by consumers as an indicator of commercial origin. If seen merely as decorative, it cannot be protected.

The Board thus suspended the appeal and referred the matter back to the Examination Division, recommending a full reassessment of whether the sign genuinely possesses distinctiveness. This procedure is explicitly foreseen by the regulation (Art. 45(3) EUTMR and Art. 30(2) EUTMIR), though it is little known outside professional practice. It has the potential to dramatically alter the outcome of a trademark proceeding.

This means that even if the opponent fails to prove likelihood of confusion, the EUIPO may still reject the trademark application. It is a form of systemic safeguard—a “second line of defense” —to prevent undeserving marks from entering the register. And this is now where the fate of Thom Browne’s trademark will be decided.

The question now seems deceptively simple: can a visually appealing, neatly structured, and well-designed sign constitute a valid trademark? According to the EUIPO and established case law, the answer is: it depends. And the Thom Browne case is a textbook example.

The case stems from the Second Board of Appeal’s decision of 1 April 2025 (R 689/2024-2), concerning application no. 17 458 837 filed by Thom Browne, Inc., and the opposition filed by Adidas AG under proceeding B 3 044 594.

The disputed mark consists of vertical stripes in red, white, and blue, framed by a dashed-line rectangle. No wording, no logos, no reinforcing verbal elements. Just lines, colors, and shape. This very aesthetic simplicity may be problematic: according to the Board, the mark is so minimal that the public would not perceive it as an indicator of the commercial origin of goods. In legal terms, it fails to “sign” the product.

This brings into focus a key concept in trademark law: distinctiveness. A mark must fulfill its legal function—allowing a consumer to say “this shirt is by Thom Browne.” If it is perceived merely as a decorative feature or a commonplace graphic element, it loses its legal function and cannot be protected.

The Board referenced a body of consistent precedent: simple geometric shapes, colored stripes, or commonly used patterns are not distinctive unless the applicant proves that the public has come to associate them with a specific commercial origin through prolonged use. This is a demanding evidentiary burden—particularly in the fashion industry, where style and trademark often blur.

The EUIPO observed that European consumers are not accustomed to recognizing product origin based on combinations of colors arranged in basic shapes. This is especially true in fashion and leather goods, where similar motifs are widespread and purely ornamental.

In Thom Browne’s case, then, style might not be enough. If the red, white, and blue stripes are not perceived as a source indicator, the trademark could be deemed invalid for lack of distinctiveness. It is now up to the designer to prove the contrary.

Thom Browne is not out of options. Even if the EUIPO finds his mark inherently non-distinctive, he still has one legal recourse: proving acquired distinctiveness. This legal doctrine is expressly set out in Article 7(3) EUTMR: even a sign that is not distinctive at the time of filing may still be registered if it has acquired distinctiveness through use.

However, this is far more than a declaration of intent. The applicant must present detailed, concrete evidence—advertising campaigns, sales figures, brand recognition across European markets, independent consumer surveys, media exposure… all of which may help, but none of which is guaranteed to succeed.

In the fashion industry, the bar is particularly high. The distinction between ornamental design and trademark is subtle. Consumers are accustomed to seeing lines, stripes, and colors as aesthetic choices rather than brand indicators. When a mark lacks any verbal element—a name or logo—convincing the Office that it functions as a trademark rather than as a fashion statement becomes an uphill climb.

For Thom Browne, this is the challenge: proving to the EUIPO examiners that European consumers view the five-striped motif as a brand signature—not a decorative pattern. If he succeeds, the trademark may be registered. If not, the EUIPO could reject it permanently, closing a key chapter in the brand’s legal strategy.

The fate of Thom Browne’s trademark remains undecided. The appeal has been formally suspended and remitted to the EUIPO Examination Division, which must now determine whether to reopen the application based on absolute grounds, as provided under Article 30(2) EUTMIR (EUIPO Second Board of Appeal, Decision R 689/2024-2, 1 April 2025).

Avvocato Arlo Canella